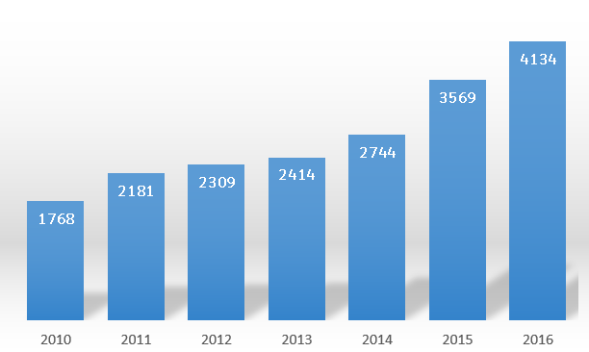

Take a walk almost any day within the streets of our major cities and the sight of a rough sleeper will almost certainly be an observable reality. The Homeless Link estimated that there were 4,134 rough sleepers during an Autumn evening back in 2016 and that number was more than double that of 2010:

Crisis research, details just how dangerous rough sleeping can be. Rough sleepers are almost 17 times more likely to be a victim of violence; women are particularly vulnerable, nearly 1 in 4 have been sexually assaulted. Additionally, many who rough sleep for prolonged periods develop complex needs that include a deterioration of both their physical and mental health.

So how did we end up in this position and what are the remedial actions that should be taken? There are numerous causes that are cited, but for now I would like to focus upon one in particular, which is possibly the primary driver to the currently situation.

The graph below shows the historic view of new houses built per annum:

What is apparent from the data is that local authority led builds fell off a cliff during the 1980s. Margaret Thatcher’s drive to move housing from the public to the private sector through the ‘Right to Buy’ scheme had a double whammy effect:

1. Critically, local authorities stopped building new houses and went into construction exile. Whilst new build volumes from the private sector and housing associations remained broadly flat (bar the 2008 financial crash induced dip), the loss of new housing supply from local authorities drastically reduced the overall supply of new homes. With supply unable to meet demand, prices invariably rose to levels which were not within the reach of the masses. ‘Right to Buy’ only works for the general populous when they are empowered to buy homes that are actually affordable!

2. Secondly, with council homes moving into the private sector, many of these same properties were rented out; in fact amidst the ‘Right to Buy’ property whirlwind, the ‘Buy to Let’ era was born. With poor regulatory oversight, landlords were all but given a free hand to place increased pressures upon tenants, not only in terms of rent value, but also in terms of the conditions of the properties rented.

So what of the solutions? Here are a couple of points as initial thoughts:

1. To start with, let’s begin with ourselves. Treat the homeless person with dignity; a kindly word can go a long way. This Guardian article provides some further practical advice.

2. The wider solution must surely be one driven by policy and the government doing the right thing. To have a roof over one’s head to protect against the elements is at its heart a fundamental human right. As a society with so much wealth, to have such a large number of individuals to be left destitute upon its streets must be a point of great shame. The matter of housing construction cannot be left entirely to the whims of the private sector, whose fundamental driver for building is return on investment and is certainly not predicated upon social conscience or needs. As such government should re-empower local authorities to build additional housing capacity according to the needs of the community. The properties that are developed should remain within the governance of local authorities who can ensure that rental rates are affordable and not subject to manipulation by market dynamics.

The government seems to agree and is trying to get a set number of houses built and is even trying to get land hoarded (allegedly) by builders released. It is also going back to the Skillcentre idea of training people to build them. But my theory is that the increased availability of mortgages and foreign investors means increased house prices. As I passed by a large empty Victorian property (owned by our council but unable to attract a buyer) I thought whether a Building Society constructed just to demolish and build anew, with a remit for the flats to be owned solely by first time buyers might help ease the situation. Finance could come from individuals or organised charities. Once the flats are sold off then the process can start again.

LikeLike

As much as I hope I’m wrong, I’m not convinced Clive, that the government gets the challenge or that it has a coherent strategy. If it did it would not be plowing money into subsidising buyers which is simply exacerbating demand (and raising prices further), where the problem is with supply. Unfortunately successive governments have ignored the fundamental challenge. The figure that’s touted is ~250,000 new build requirements per annum to meet the shortfall. If we had the historic local authority builds which was around the 100,000+ mark, we probably would not have a problem. Period. A dual benefit of supply met and also sufficient quantities in the public sector to ensure that ‘public good’ principles are applied to a sizeable portion of rented properties.

LikeLike